What True Grit Really Means

A Mostly True Essay by Marci Henna

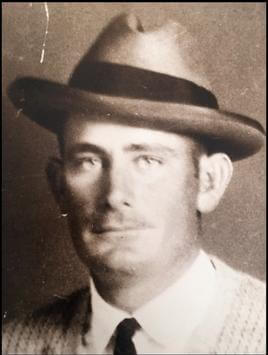

My grandfather was a crusty rancher whose personality, looks, and charm were a cross between John Wayne’s Rooster Cogburn (True Grit) and Jack Palance’s Curly Washburn (City Slickers). He was the descendant of two generations of Texas Rangers and the son of a gentle, story-telling cattleman and his stubborn, hardworking wife. Like most Texans who were born in the late 1800s and early 1900s, his family had little cash but lots of offspring. He became the baby in a flock of ten children three times over as each of his younger siblings passed away. There would be four who would die before they’d gotten a toehold in what the Old Testament refers to as the fullness of time. His mother’s hours were overflowing with gardening, canning, cooking, ranching,

child-bearing, and parenting. In that era, it was a common practice for older children to raise their younger siblings, and therefore not surprising when his rearing was assigned to his beloved sister. He would think of her as his mother for the rest of his life.

In the sixth grade, he quit school so he could work to help support the family. When his efforts on the ranch weren’t lucrative enough, he hired out in the oilfields of West Texas and lived in a tent. Nevertheless, he continued to expand his mind. Even into his late eighties, he would study books and articles about astronomy, Jesse James, Scott Cooley, Quanah Parker, Lead Belly, Hank Williams, and Jimmy Rogers.

Like Walt in When We Last Spoke, he could pick up a rattler by its tail and crack it against the ground, killing it before it had a chance to recoil. However, his most feared foe was harder to whip than any snake. He fought the Great Depression without gloves and lived to tell the tale, though it left its mark upon every financial decision he ever made. In his book, the Great Depression was the GREAT WAR. His personal story could be read by everyone who witnessed the burdened slope of his shoulders or the way he cautiously managed each penny that passed through his household. Bits of rope, rusted combine parts, and Folger’s coffee cans filled with old, misshaped nails lined his workshop. If washers, nuts, and bolts were needed, chicken and barbed wire lay coiled in a pile. Old tires that could become swings for youngsters or possibly turned into planters waited in the corner.

Inside the house, soap ends were melted and made into new bars. Tinfoil was washed and reused. Empty milk cartons became containers for frozen chicken parts or creamed corn from the garden. Everything had more than one purpose, the sum total of which was intended to protect the family from future economic disasters. Nothing was wasted. All was saved. Just in case…

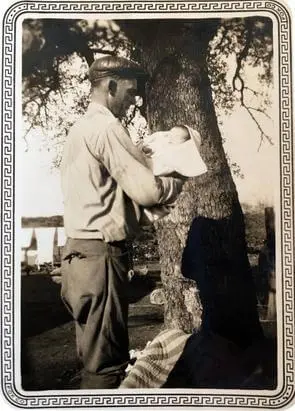

After the Great Depression eased enough, he planted a large peach orchard. During harvest time, he’d pick peaches all day, eat dinner and sleep until two a.m. Then he’d drive a truckload of barely turned fruit to the market in San Antonio. By dawn, he was set up to sell his Clings or Freestones to local grocers. After selling that day’s inventory, he’d drive down the long road back to Blanco County, pick more peaches and do it all over again.

His was a hard life, but he had the kind of grit it took to see it through. When his spooked horse threw him onto limestone and fractured his back, he spent months in the hospital. When finally released, he went right back to the ranch, mounted the same horse, and rode out to check on cattle. It must have taken galvanized steel in both spine and spirit to accomplish that, but he was determined not to be whipped by mere circumstance. Like Curly Washburn, he had a toughness that had, in part, come from experience. Mainly, he had been born knowing he was tough. It was in his DNA.

I loved my grandfather in all his crustiness. A crust always supports a sweet peach pie to keep its filling in place. This is what I know: beneath that tough exterior was a man with a soft underbelly.

Whenever my sister and I stayed with our grandparents, we looked forward to the noonday meal and Paul Harvey’s voice telling us, “The Rest of the Story.” The anniversary clock ticked on the mantle while steaming bowls and platters of food were laid out. Next to the table, a flyswatter stood ready like a gun in a holster should flies try to land. We fidgeted, waiting for him to come inside, remove his straw hat and wash his hands with Lava in the kitchen sink. Often, he needed prompting to change gears and join us. My grandmother would lean out the screen door and call, “Come in and eat before I throw it to the hogs.”

O how we loved the fried chicken, butternut squash, and blue-ribbon beefsteak tomatoes that melted in our mouths. Our favorite part was dessert—usually golden westerner cake or pecan icebox cookies covered in peach slices that never failed to send us into a food coma. After our eyes drooped, we were sent to take a nap. However, just as soon as our young heads touched our pillows, all that sugar kicked in, and we became robustly mischievous.

He would hear us giggling and acting silly and eventually reappear to grant us reprieve. He’d lead us into the kitchen, lift us up onto the counter top and let us dip our hands into a full jar of peppermint candy that stood near the broad electric stove. The fact that he gave us more sugar made him a hero in our eyes. We were sworn to secrecy and warned not to tell our grandmother lest she skin him alive. Like Ruby in When We Last Spoke, she was five feet tall with her shoes on and the sweetest woman to ever walk God’s green earth. He has six-feet-four and would carry on as his life hung in the balance were we to rat him out. Of course, she knew all along and hadn’t minded one whit.

Some Sunday mornings, I’d find him looking blue. He’d be sitting in his living room chair, thinking about his past—the mistakes he’d made, family members he’d buried, and perhaps missed opportunities. He’d turn on the record player and listen to Ernest T. Ford sing “How Great Thou Art,” “In the Garden,” and “Amazing Grace.” Then he’d spin Hank Williams’ “I Saw the Light, and Patsy Cline’s “Just a Closer Walk with Thee.” They became his choir and his living room, a sanctuary that somehow made him feel better. Occasionally, his methodology was supplemented by Billy Graham’s crusades with George Beverly Shea singing “Just as I Am” on his old RCA TV. Sightings of him in the Methodist Church had long been rare as snow in the Texas Hill Country, but he was a believer. He believed in God, the value of hard work, self-education, and the true grit of perseverance.